TAKING CORRUPTION BY THE HORNS: Lessons from Our Neighbors

Bobby M. Tuazon*

Director for Policy Studies

Center for People Empowerment in Governance (CenPEG)

(Paper for the second anti-corruption summit of the broad Coalition Against Corruption at the Diamond Hotel in cooperation with the Presidential Anti-Corruption Commission, Oct. 12, 2018)

My brief presentation will center on lessons in the fight against corruption from selected Asian countries based on reputable studies and surveys published in recent years. In the end, my paper will underscore the imperative of closely integrating the fight against corruption with a serious program toward economic equality or a people-centered economic growth.

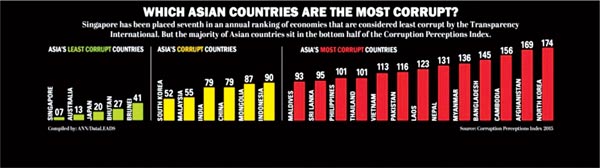

Let me start with a review of the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI, Feb. 2017) by Transparency International in some selected Asia Pacific countries.

Corruption Perception Index 2016 (CPI), Transparency International

SELECTED ASIAN COUNTRIES and CPI SCORES (2016)

*CPI score ranges from 0 (very corrupt) to 100 (highly clean).

Source: Jun ST Quah, Singapore

The data above show that Singapore is the only Asian country among the top 10 least corrupt countries in the world. Singapore is followed in Asia by Australia, Japan, Bhutan, and Brunei. (Hong Kong, a Special Administrative Region or SAR of China, is also known for being least corrupt.)

Citing the CPI, several of Asia’s 48 countries fall in the most corrupt countries in the world including Cambodia, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Nepal, Laos, Pakistan, Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Maldives, and North Korea.

Countries at the bottom of the CPI show poor performance in curbing corruption due to weak or lack of government accountability, lack of oversight, shrinking space for civil society or NGOs, and the marginalization of anti-corruption action aside from threats faced by anti-corruption agencies (ACAs).

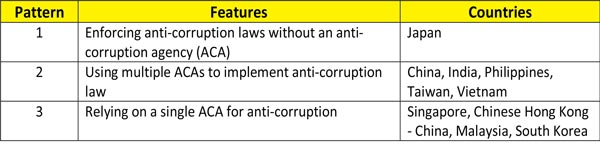

PATTERNS OF CORRUPTION CONTROL

IN SELECTED ASIAN COUNTRIES

Source: Jun ST Quah

The table above shows that countries in Asia with multiple / several anti-corruption agencies (ACAs) still lag behind in anti-corruption and even fall under the most corrupt countries. Those relying on a single but independent ACA, however, are the least corrupt countries.

Singapore is the typical example of having a single but independent ACA – the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) whose birth dates back to 1952. Although the only corruption watchdog, the CPIB has a comprehensive set of responsibilities. Its responsibilities include policy development, research, monitoring and coordination of implementation measures, preventing corruption in power structures, public education and awareness raising, and investigation and prosecution of corruption cases.

Studies show that the ACAs of Singapore as well as Hong Kong-China are effective because of their leaders’ strong political will; and having a strong capacity in terms of adequate budget and personnel. For instance, since its establishment in 1974, Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) has increased its budget 58 times to US$120M while the number of its personnel rose four times to 1,358 in 2014.

SINGAPORE CPIB’s BUDGET & PERSONNEL (2008 & 2015)

Source: Jun ST. Quah

Single ACAs that perform well also enjoy operational autonomy with no political interference and hence perform their role impartially. Singapore’s CPIB uses a total approach in dealing with all corruption complaints – “big and small cases” and both “giver and receiver of bribes.” On the other hand, Hong Kong’s ICAC has a strong community relations department (CRD) to enhance public confidence in anti-corruption as well as to sustain public support to its campaign.

Indonesia (pop.: 270 million) has its Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi or KPK) founded in 2003 or five years following the fall of the country’s long-drawn authoritarian regime. Today, the KPK is Indonesia’s most trusted institution with a 100 percent conviction rate. The commission’s work has led to an improvement in Indonesia’s CPI from 107th in 2015 to 88th in 2016. The KPK enjoys a favourable public support which is important as the commission tries to thwart institutional hurdles such as attempts by some members of the House of Representatives as well as the police to weaken its credibility. The bigger challenge to the KPK, however, is how to contend with corruption that persists in the country’s local government politics run by political families. To recall, Indonesia entered its transition to democracy in 1998 following the fall of the 33-year Soeharto dictatorship which nurtured corruption, plunder, nepotism, and political dynasties whose roots have not been completely cut until today.

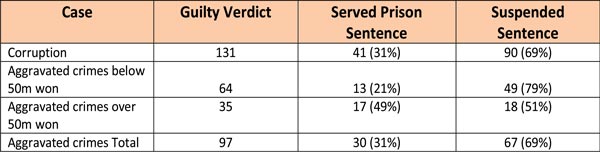

Having a single ACA, however, does not automatically guarantee a positive achievement in anti-corruption. South Korea, which maintains a single ACA, still faces serious problems in the efforts to curb corruption. One institutional obstacle is the merging of its single ACA – the Korea Independent Commission Against Corruption (KICAC, 2002) – with the Ombudsman and Administrative Appeals Commission to form the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (ACRC) in 2008. This resulted in diluting KICAC’s role creating gaps in its function and weakening a coherent policy. Other reasons cited are the lack of a political will and low priority given to investigating corruption cases. (The table below will explain this particular dilemma.)

But in recent years, massive public pressures led to the prosecution of the country’s high officials for corruption including former President Park Geun-hye.

SOUTH KOREA: PUNISHMENT OF PUBLIC OFFICIALS

FOR CORRUPTION (1993-2004)

Source: Jun ST Quah & Joongi Kim

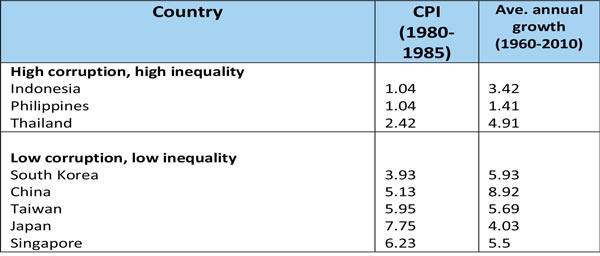

Socio-economic and political roots of corruption

At this point, let me emphasize that any policy action against corruption should begin with a clear understanding of a country’s social, economic, and political conditions and how such conditions breed a systemic corruption with deep roots. I am talking about the causal relationship or bidirectional causality between economic equality and corruption: high inequality breeds high corruption, high corruption sustains high inequality.

Especially for developing countries, one cannot fight corruption without fighting poverty and income inequality. A study of sample 97 developing countries covering 997-2006 (“The Causal Relationship between Corruption and Poverty: A Panel Data Analysis,” 2010, Malaysia) reveals that corruption and poverty are entwined with a bidirectional causality. (A causes B and B causes A indicating a bidirectional or cyclic causation). This means, social and income inequalities in poor countries generate greater imbalances in the distribution of power and encourage corruption. Poverty invites corruption as it weakens economic, political, and social institutions. In turn, corruption deepens poverty by hampering productive programs.

Consequently, poorer countries may not effectively fight corruption due to lack of resources.

Likewise, countries with high inequality are more likely to suffer from bureaucratic patronage and corruption. Bureaucratic patronage and clentelism will increase bureaucratic corruption.

GROWTH PERFORMANCE BY CORRUPTION

(CPI 1980-1985)

and INEQUALITY

Based from Jong-sung You (2015)

Economic growth alone, however, will not necessarily result in lower corruption unless growth per se is accompanied by serious political reforms that distribute economic and political opportunities and resources to the vast majority of population thus resulting in the empowerment of the people and in the marginalization of the powers that be. Yet another needed reform is the institutionalization of meritocracy in government service as well as in other sectors of society as a means of weeding out political patronage and undue influence as well as tapping the brains, skills, and hard work of those who deserve to render public service for the good of the country.

It is necessary to address the integrated strategy to reduce poverty and fight corruption. In other words, the attempts to reduce poverty must be complemented by serious efforts to reduce corruption.

To illustrate my point: In the aftermath of World War II, South Korea, Taiwan and the Philippines were all similarly poor, very corrupt, and highly unequal. In fact, the Philippines had higher per capita income and substantially higher educational attainment than the other two countries. Then, what happened? Both South Korea and Taiwan implemented far-reaching land reforms in the 1950s-1960s, while the Philippines failed to do so. Land reform in South Korea and Taiwan dissolved the landed elite and created relatively egalitarian societies; they also initiated industrialization that catapulted them to newly-industrializing countries (NICs) later. Meanwhile, both countries – being the inheritors of Confucian ethics – adopted and popularized meritocratic bureaucracy that gradually led to a decline in corruption.

The hard lessons

We don’t need to adopt Western models in the continuing fight to eradicate this social scourge called corruption. All that needs to be done is to draw lessons from our neighboring countries especially those that can share us their own success stories. We should develop our own models and approaches based on the specific characteristics and attributes of the Philippine society and its political system.

To summarize these lessons:

A single ACA is the more effective organizational approach in fighting corruption. Such structure, however, should undertake comprehensive responsibilities which it can only do by having vast powers and being supported by a stable budget, personnel, and other resources. Countries whose leaders show a strong political will, where support is given by other institutions so that the anti-corruption agency can perform its work impartially and without political interference, and where there is a strong public support to anti-corruption show effective performance in anti-corruption.

Anti-corruption, however, must have a strong foundation of economic growth, income equality, and where political patronage is successfully disenfranchised. Economic growth and income equality go hand in hand with the fight against corruption.

There should be no illusion, however, that corruption can be eradicated overnight. But it should be pursued patiently and painstakingly across generations and by meeting the key requirements and conditions as mentioned such as having a credible, publicly-supported anti-corruption agency.

--------------------------

*Bobby M. Tuazon is a professor of the University of the Philippines (Manila) where he used to serve as head of the Political Science Program. Tuazon has also been cited as Outstanding Teacher in UP Manila eight times. He gives lectures and serves as resource speaker in various universities and conferences abroad including the US, Europe, and Asia. He is the editor and co-author of 16 books on governance, foreign policy and security, human rights, peace process, and other areas.

- Smartmatic and the Venezuela Electoral Fraud

- Venezuela's Maduro Accuses Smartmatic of Caving to US Pressure

- What could have been done

- SUMMER IN BIKOL FIELDS Learning governance at ground level

- Prospects and Intricacies of a Peace Agreement in the GPH-NDFP Negotiations

- THE CIA IN THE PHILIPPINES: A BRIEF HISTORY

- Military intransigence in the peace talks

- Slim chance of deal in peace talks

- Revisiting Istanbul Principles and its Relevance to Philippine CSOs

- Paving the Way for Philippine CSO Development Effectiveness Work

- THINK TANKS PRESS FOR BILATERAL CEASEFIRE AGREEMENT

- Now more than ever, resume the peace talks!

- The judicious spending of taxpayers’ money: Does it matter?

- ‘Narco politics’ cannot be invoked to replace the people’s right to vote

- Probing presidential platforms

Center for People Empowewrment in Governance (CenPEG), Philippines. All rights reserved