SPECIAL REPORT

Cast of Clans: From Aguinaldo to Aquino, dynasties rule

By: Lira Dalangin-Fernandez, InterAksyon.com

December 19, 2015 11:31 AM

InterAksyon.com

The online news portal of TV5

Posted by CenPEFG.org

Dec. 22, 2015

MANILA, Philippines -- From the country’s first president, Emilio Aguinaldo, to Benigno Aquino III, the incumbent, Philippine politics has always been essentially a family business.

And, by all indications, the May 2016 election is unlikely to change this.

A new study by the Center for People Empowerment in Governance, or CenPEG shows political clans firmly entrenched in 72, or 94 percent, of the 77 provinces included in the research.

And upstarts are constantly emerging. Of the 178 dominant political families named in the study, 100, or 56 percent, come from the old elites; 78, or 44 percent, are new.

CenPEG, a public policy center, furnished InterAksyon.com an excerpt of its study, “Political Families and Philippine Politics,” which it will release in full to the public early next year.

The study says a political family exists “if at least two members of the same family (typically up to the third degree of consanguinity) have won a congressional and/or gubernatorial seat between 1987 and 2010.”

An individual who has won at least three times as representative and/or governor during the same period and who has a relative who served as president, vice president, senator, representative or governor in the post-war years is also deemed to belong to a political family.

“The study will enhance or enrich the popular knowledge about the persistence of dominant political families all over the Philippines,” Bobby Tuazon, CenPEG director for policy studies, said.

“The deepening part of it is that we would (know) that there are many … families that remain dominant, and they usually rule politics, including electoral exercises, since EDSA 1, meaning from 1987 to 2010,” he added.

The research also used data drawn from the Human Development Index studies published in the Philippines Human Development Report 2008/2009 to look at the possible relationships between electoral outcomes and three indicators of human development: income, health and education.

The result? “Whether a province is economically rich or not, whether it is a poor province, the persistence of political dynasties is the same,” Tuazon said.

A major finding also revealed that in provinces where dominant political families exist, private armies --or “private armed groups” as law enforcement refers to them -- also persist.

“But this is not exactly to say that there is a correlation between PAGs and political dynasties; what we mean is that in those provinces dominated by political dynasties, those are the locations where you can find the active PAGs,” Tuazon said.

Where the dynasties are

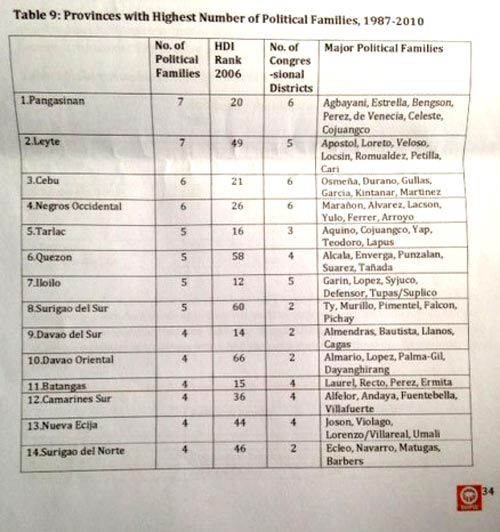

Of the 14 provinces with the most number of political families, six are in Luzon, four in the Visayas, and four in Mindanao.

Seven of these provinces belong to the top 30 percent HDI performers (Pangasinan, Tarlac, Batangas, Cebu, Iloilo, Negros Occidental, Davao del Sur) in 2006; four are in the mid-level rankings (Nueva Ecija, Camarines Sur, Leyte and Surigao del Norte); and, three (Quezon, Surigao del Sur and Davao Oriental) are in the lowest 30 percent.

Most of the dominant clans in the Luzon and Visayas provinces are old names. “Many of the elites in these provinces trace the origins of their power back to the colonial era and the post-war years when their forebears commanded the most influential elective and appointive positions in government,” Tuazon explained.

Surigao and the Davao provinces, on the other hand, have a bigger mix of old and new families, reflecting their “frontier” origins when Mindanao was opened to settlers from other regions more than half a century ago.

Firm grip

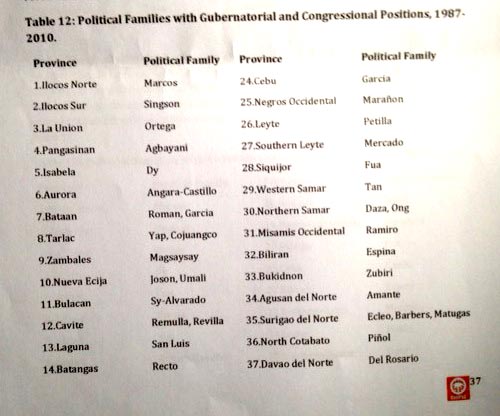

An indicator of the power and reach of political families is their ability to control the two top posts in a province: the governorship and congressional districts.

“In the hierarchy of power and patronage flows, controlling these two elective positions ensures easier access to national resources, while at the same time facilitating control on the ground,” CenPEG said.

“When these two positions are not controlled by the same family, intense factional struggles oftentimes ensue,” it added. “It is not surprising, therefore, that political families aim to control these two pivotal positions.”

Of the 77 provinces in the study, 46, or 60 percent, had families that won these two positions at various times from 1987 to 2010.

Merry-go-round

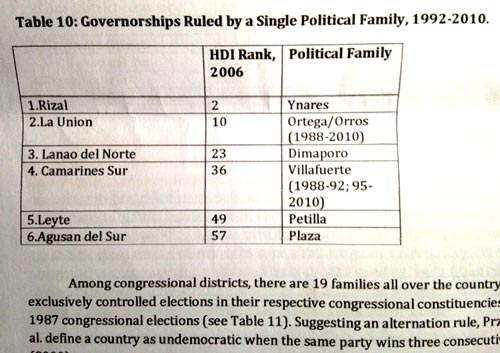

Some political families entrenched themselves during the restoration of elections in 1987 and have continued to maintain their grip on the posts of governor and district representative to this day.

In six provinces -- Rizal, La Union, Lanao del Norte, Camarines Sur, Leyte and Agusan del Sur -- the governors have all come from only a single family since 1992.

Three of these provinces have high income, health and education indicators, the rest have low HDI scores.

“Such overpowering dominance by these families is exemplified by the Ortegas of La Union,” CenPEG said. Since 1998, members of the clan have won all gubernatorial contests. Family members have also won the province’s first congressional district from the 1969 to the 2010 elections.

“The family has become a permanent fixture in the political life in the province” since 1901, early in the American colonial era, when clan patriarch Joaquin Ortega of the Partido Federal was appointed governor.

Monopoly and poverty

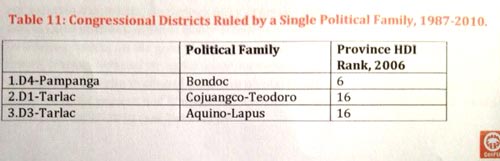

“If political families can be considered the functional surrogate of political parties in the country, then one has to be alarmed by the same families winning elections for no less than eight consecutive terms or 24 straight years,” CenPEG said.

Indeed, such a monopoly on power cannot bode well for any place as the study shows.

For instance, at least six congressional districts in Siquijor, Albay, Camiguin, Sorsogon, Negros Oriental and Davao Oriental with relatively low to very low HDI achievements are controlled by clans who are “perpetually elected in these depressed areas.”

Provincial pork

Before the Supreme Court declared the Priority Development Assistance Fund unconstitutional in 2013, lawmakers enjoyed the institutionalized funding of the pork barrel, with senators receiving P200 million each annually, congressional representatives, P70 million.

But even with the PDAF stricken from the national budget, representatives still get a crack at funds by proposing pet projects to line agencies and using their endorsement power to allow constituents to avail of health and other services.

Local government officials, on the other hand, have their internal revenue allotments, as provided for by the Local Government Code, to draw from.

“While its amount depends on the revenues collected by the Bureau of Internal Revenue and the standardized distribution formula provided for in the Local Government Code, the IRA constitutes a significant financial resource for local politicians, especially in the face of weak accountability mechanisms for the expenditure of such resource,” CenPEG said.

Then there are the Allocations to Local Government Units (ALGU), among the items classified under the Special Purpose Funds or SPF, a lump sum appropriation in the national budget.

Inclusive of the IRA, which is automatically given to local government units, the ALGU accounted for P360.54 billion of the 2014 budget.

Dispensed at the behest of the President and the Budget secretary, and lacking any clear audit on how it is spent, the ALGU presents a Pandora's Box just as complex as the pork barrel issue, an earlier report by the Citizen Action Network for Accountability said.

The enduring primacy of dynasties

The CenPEG study quotes historian Alfred McCoy to provide an apt summary for the enduring prominence of the family and the kinship network in the entire range of activities in the country’s political, economic and cultural life:

“In the century past, while three empires and five republics have come and gone, the Filipino family has survived. It provides employment and capital, educates and socializes the young, assures medical care, shelters its handicapped and aged, and strives, above all else, to transmit its name, honor, lands, capital, and values to the next generation.”

“But a state that is anchored on families and clans with narrow and exclusivist interests and loyalties is bound to create difficult problems for state formation and democratization, particularly, in the absence of strong national political institutions,” the study notes. “Moreover, the accountability mechanism that forms a key aspect to the democratization process becomes short-circuited by narrow kinship loyalties rather than legitimized by broad citizens’ choices.”

“In the Philippine context, a key political mechanism used to negotiate contentious state-society linkages driven by powerful family and clan interests has been an electoral process fueled by pervasive system of patronage linking national and local political elites,” it says.

Trying - and still not succeeding - to rein in the clans

In May 2014, after two decades in the legislative mill, the bill banning political dynasties reached the plenary of the House of Representatives.

The proposed measure would allow only one member of a family to seek office at any given time.

It would be similar to a "holding room" for political clans "and prevent them from running until after their incumbent relative shall have finished his or her term," Capiz Representative Fredenil Castro, chairperson of the committee on suffrage and electoral reforms, said in his sponsorship speech for House Bill 3587.

Castro stressed that the bill would "provide equal access for opportunity for public service" and serve as a "regulation" and not a "prohibition" to political families.

"The members of Congress are now being called to comply with their constitutional mandate to pass an implementing law pursuant to Section 26, Article II of the Constitution to abate the impact of political dynasties in our country, which according to studies, are responsible for the many ills experienced and will continue to be experienced by the Filipinos if left unabated or unregulated," he said.

"This provision is no less than an admission in clear terms ...of the menace that political dynasties may bring or have brought and which continue to plague this country if unregulated," he added.

Not surprisingly in a chamber generously populated with members of dynasties, a year and a half after making it to plenary, the bill remains stalled and is not among the priority measures the 16th Congress intends to pass in its remaining few weeks.

There have also been attempts to amend the bill to allow up to three members of a family to run within a “jurisdiction.” Backers of the amendments said offering a “looser” bill would increase its chances of approval.

Minority Leader Ronaldo Zamora said it is too late for this Congress to pass the anti-dynasty bill. “You don’t want to do it before an election, let’s do it next year, after the elections,” he explained.

Zamora himself does not favor a very strict definition of a political dynasty, proposing that other family members may run in the same election if they do so in different jurisdictions or areas.

“The important thing is to put it on the law, that’s what I’d like to do,” he said.

Without a law in place, when May comes around, voters will likely see themselves limited to the same names to choose from.

Unless they actually wield the power of the ballot to reject dynastic rule, which, unfortunately, appears unlikely.

http://www.interaksyon.com/article/121639/cast-of-clans--from-aguinaldo-to-aquino-dynasties-rule

- Probing presidential platforms

- Conference calls for people-centered policy actions for Asian development and peace

- WWII 'comfort women' urge visiting Japanese emperor: OFFICIAL GOV’T APOLOGY, UPHOLD TRUTH, and JUST COMPENSATION

- FEARLESS FORECAST (EPISODE II): Comelec will not comply with e-Commerce Law in 2016 elections

- Fearless forecast: Comelec’s non-compliance with the AES law in 2016 (last of 2 parts)

- Fearless forecast: Comelec will not comply with the AES law in 2016

- CenPEG releases travelogue

- Experts: Nuisance bets reflect disillusionment, uneven playing field

- Partylist solon presses for tax cuts

- The True Cost of a Political Campaign

- Management decisions: Based on RA 9369 or purely Comelec’s?

- CenPEG holds 1st roundtable with media on presidential poll results

- Filipino IT can do it!

- FIT4E: The only transparent solution

- Realpolitik in the maritime tiff

- China’s challenge to PH sovereignty

- Choosing the next president

- Fixing the presidency, reforming the state

- New Comelec chair says he’s open to other election technologies

- SC ruling on AES Watch Pabillo and IBP vs Comelec, Smartmatic-TIM

- Comelec must explain P3.2B unliquidated cash advances

- CONGRESS ASKED TO HOLD DEMO ON PCOS HACKING

- 25 Bishops ask poll body to stop midnight deal with Smartmatic

- Pope Francis: reform and conversion

- 2 poll watch coalitions stage rally vs Comelec-Smartmatic midnight deal

- AES Watch questions Comelec-Smartmatic midnight deal

- ASEAN-India: Building Youth Partnerships through Culture and Entrepreneurship

- CenPEG forges research exchange and partnership with Jinan University

- FOI: Bearing fruit or foiled again?

- Remittance with Representation: The right to vote of overseas Filipinos

Center for People Empowewrment in Governance (CenPEG), Philippines. All rights reserved